“Bwa pin means pinewood in Kreyol.

It’s sold in the market as little bundles of faggots. I don’t know how bwa pin was used before the earthquake, maybe in the same way it is now, but now it is something people buy to burn in order to clear the air of foul smells, and foul smells are everywhere, the smell of rotting fruit is almost worse than the smell of rotting corpses, and then there’s the gasoline, and all the shit and piss.

I find it easier to grasp the weight of existences and the weight of a disaster through small and workaday items. Although Haiti is severely deforested, bwa pin is not expensive. I think it cost 100 gourdes for eight or nine bundles of bwa pin.

In any case, when I was there I did not have the money to stimulate Haiti’s economy with the purchase of lavish souvenirs and fine handiworks made of salvage materials, although these are very impressive, usually made by children, sold everywhere, and buying them is good for the people who make them.

What did I bring back with me.

I brought home spicy peanut butter, cigarettes, and bwa pin. I also brought home the gifts that my friends gave me, one stolen book on Haitian art, one purchased copy of The Waste Land and Other Poems, bought from a lady off the street and stamped with the name of a secondary school, The Waste Land, either an irony or a ‘poetic justice’ I couldn’t quite resist. And there was a homemade French/Kreyol language book, and a bag of weed I forgot I had, I walked right onto the plane with it in my pocket.

One day Sadrac’s motorcycle stopped working, I forget where I needed to go, where he was taking me. Maybe a support group for rape survivors that a

journalist had told me about. We were near the Champs de Mars camp, where an estimated 25,000 people now live. Champs de Mars used to be a stately park with avenues and museums alongside it; it’s near the bright white presidential palace, which of course is ruined now. A bookseller I met across from the camp said, this place has already become a ghetto. On one side of the sprawling bumpy rows of bedsheet and plastic houses there is an outdoor nightclub with a trandy gogo dancer; kompa music plays very loud there every night.

Sadrac and Billy and I walked to the place where the motorcycle could get fixed. I think I was thinking the motorcycle stopped working because Billy was on it with us, and a friend has warned Billy that he’s fated to die on a motorcycle. Not on my watch, I was thinking, not on my watch. We were in a corner of Champs de Mars, along the perimeter. On one side of the corner was the motorcycle mechanic, where there were many motorcycles and the men who ride them. It hurt to breathe because of the gasoline and smoke. On the other side of the corner were eight overflowing latrines. In the middle of the corner were four or five shelters where families live. A woman outside of one of the shelters was scrubbing clothes in a plastic tub and burning bwa pin. The smell of butninh pinewood is high and sweet, and it clears away the smell of exhaust and the smell of shit. The burning of bwa pin, along with cooking and laundry, is what women do. If women did not do this work in a world where a million people are homeless, it would be all shit and all motorcycle exhaust, and everyone would murder each other from disgust and rage.

I played with a few teenage girls near where we could smell the bwa pin, a couple of handclapping games, and they kept singing the same part of this one song that goes “ANBA DES KAYES MANMAN” (UNDER THE RUBBLE, MAMA. or somethng like that), which was a popular song in post-earthquake Haiti. I had a bag of candy and I gave them some, big starlight mint balls we were all sucking, so dehydrated our mouths got sticky and filled with drool. One girl kept squeezing a healed gash on her thigh until it bulged. I asked her about it. Dans l’evenman, she said distractedly, it’s from the Event.

The Event is the way most people I talked to refer to the earthquake. They also call it Ghoudoughoudou, because, they say, that’s the sound it made. Really, you say, really, it sounded like that. Yes, they say. And then they say, there’s no way to describe what it sounded like.

Then something bad happens. After that something good happens. The air is so bad you can’t breathe, and all of a sudden it’s sweet. Everything indescribable stays that way, and the secrets stay secret, right there in full view with the scars and garbage, everything that hides in human bodies and everything that hides them, inside out, broken and mysterious, for a very very long time.”

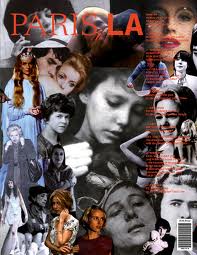

Excerpt from Some of My Faults, for Haiti by Ariana Reines published in the new issue of PARIS, LA #5.