Douglas Crimp—art historian, essayist, educator, author (Before Pictures), editor (October, throughout the 1980s), curator (Pictures)—died this morning in New York City.

“[In Before Pictures] I was interested in putting together two aspects of my life that were fairly difficult to negotiate in my first decade in New York—my art-world self and my gay-world self—at a time when both those worlds were highly experimental. I experienced innovation, experimentation, and transformation in the queer world and the art world simultaneously but mostly separately. I had to figure out how to make my two worlds, if not cohere, at least not be absolutely in conflict. My hope for Before Pictures is that it will provide a ‘queer history’ of both these worlds by putting them in conversation. I expect it might change how we think of 1970s gay culture, which we know mostly from the work of historians who write about the flourishing of gay politics. It might also change how we think about the art world of the ’70s.

“I had several different motivations for writing the book. One is that, in my ACT UP days, I made a whole bunch of younger friends, people mostly twenty years younger than me. I experienced the extraordinary explosion of gay culture during the 1970s, but they didn’t. I talked about it, they asked me about it, and on a couple occasions people said, you should really write about the gay ’70s in New York. That is not only because of their interest in what I was saying but because we were all horrified by the new narrative that was being put in place by gay conservatives. This narrative held that the ’70s represented our immaturity, an immaturity that led inevitably to AIDS, which in turn made us grow up and mature, become good citizens who wanted to get married and settle down and behave ourselves. I opposed that narrative in all of my AIDS writing.” — Douglas Crimp, interview by Jarrett Earnest*

“It has always seemed to me, given what little I understand or have experienced of seeking sexual partners over the internet, that people not only advertise who they want to appear as, but also believe they truly know who they are and what they want. What I took from the gay liberation ethos was that we didn’t know who we were and we didn’t necessarily know what we wanted. Instead, we felt we should be open to everything, even things we thought we didn’t want, which might open you to partners of different races, to differently abled partners, and certainly to people with different sexual proclivities. I tried many things that frankly I was quite repelled by, but I was just being a good liberationist, thinking, ‘OK, I can’t say, No, I don’t do that, or That’s not who I am.’ I didn’t necessarily seek such things out a second time, but I often surprised myself. I guess that would be my question to you: How much do you surprise yourself?

“My experience of diversity and of racial discourses was all in my queer life, not in my art world life. The latter was a very white world, no question. There only began to be a consciousness about the paucity of women artists and numbers of black artists in the Whitney Biennials around that time. We’ve moved some from there. It was also the time when the Museo del Barrio was founded as a response to the lack of diversity in the mainstream art world. But I would have had to go pretty far afield from my own activities and experience to bring that stuff in. So it really came in terms of my other life, essentially. I experienced that as just one of the really big differences between the kind of people I knew in the art world and the kind of people I knew in the queer world…

“The interdisciplinary or hybrid quality of the memoir flows from that juxtaposition that started with the first chapter, in which I discuss what I call ‘my two first jobs,’ haute couture with Charles James and conceptual art with Daniel Buren at the Guggenheim; two seemingly incommensurate things, I use that sort of incommensurability throughout as a means through which to interrogate both sides. I do this in the chapter about [George] Balanchine and [Jacques] Derrida, for example. The idea was that juxtaposing the gay world and the art world would unsettle the standard narratives of each and then come up with a different kind of history of both. I’m hoping that is what the book accomplishes. It’s a history of New York in the 70s, it’s a very personal history, but I think it is also a broader history.” — Douglas Crimp, interview by Malik Gaines**

See Crimp on Trisha Brown.

See David Velasco on Crimp.

*”Douglas Crimp with Jarrett Earnest,” Brooklyn Rail, 2016; reprinted in Jarrett Earnest, What it Means to Write About Art (New York: David Zwirner Books, 2018), 102–118.

**”Conversations: Douglas Crimp and Malik Gaines,” Document 9 (Fall-Winter 2016): 130–133.

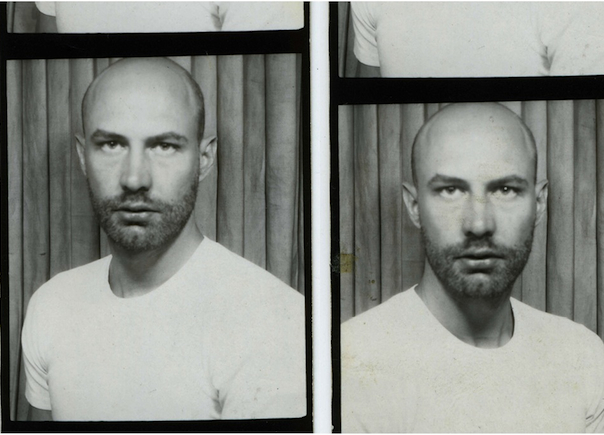

From top: Douglas Crimp in the 1970s; book covers, MIT Press (2); Crimp in his loft on Chambers Street, downtown Manhattan, circa 1975; book covers, MIT Press (2); Crimp (right) and Daniel S. Palmer in New York City, 2016, photograph by Katherine McMahon; book cover University of Chicago Press and Dancing Foxes Press; Pictures exhibition catalog, Artists Space, 1977. Images courtesy and © the author’s estate, the photographers, and the publishers.